As I’ve written about racism and posted about it on social media, I have been reminded that not all people believe that racism even exists.

You may be shaking your head, saying: Come on, Kristin! Why do you keep beating this drum! I’m not racist. Racism is a thing of the past. All this talk just serves to further divide us.

I disagree, and I think our denial of racism is further evidence of its insidious nature — proof that it is way beyond individual acts of prejudice to being deeply rooted in our collective ideology.

Over the past couple of weeks in this space, I have explored the use of Critical Race Theory in the classroom. Some may think I use this framework principally because I teach Black students, but that’s not true. I would use CRT and other antiracist strategies in any classroom — even if my students were all white.

Why? Because racism impacts all of us — most dramatically and tangibly people of color, to be sure, but no less tragically white people.

Think about it. Way back when European explorers came to this continent, they saw its beauty and expansiveness and determined to have it for themselves. Native Americans, of course, had been inhabiting this land for quite some time, and surely some colonists befriended them and sought to share the land peacefully. So, what happened? How did Native Americans end up being called ‘savages’? How did it happen that as this land was being ‘settled’, countless Native Americans were killed or displaced?

Do we ask these questions in school? Or do we take at face value the fact that colonists came to the continent, met the Indians, had Thanksgiving, and, yeah, there were a few massacres here and there, but ultimately the white people got the land and lived happily ever after?

Do we assume that the white people made out pretty well? Certainly, they got what they wanted. Whatever actions they might have taken toward the Native Americans — assimilation, displacement, or the decimation of an entire people group — had little negative impact on the white people, right? Or did they? Did the ‘success’ they found feed the belief among white people that if we want something and fight hard for it, it can be ours? Isn’t this the American Dream? Don’t we all aspire to dream big and succeed, just like the early explorers did? Does it matter if our success comes at someone else’s expense? Isn’t it a dog-eat-dog world, survival of the fittest and all that?

Are we proud of this characteristic of the American ethos? Do we want to perpetuate it further?

What if in teaching this history to American students we asked some questions? What if we sat at a table, map spread wide, and examined what happened? What were the Native Americans doing? What were the white people doing? Who had the right to be on the land? Who won? Who lost?

A question-based strategy such as this, which is informed by Critical Race Theory, encourages learners to ask questions that enable them to see a fuller picture of the story, from more than one perspective. In asking questions, students become critical thinkers. As they ask questions, they find they have more questions: What happened to the Native Americans next? What impact did the colonists’ actions have on their lives? What long-term effects did these events have on the Native American people as a whole?

In asking such questions, students might discover that colonization had a dramatic impact on Native Americans. They might discover the practices connected to Native American residential schools, legislation impacting Native American tribes, and statistics around addiction and suicide among Native American people. They might connect some dots and realize that when we ‘fight for what we want’ and ‘win’, almost without exception, someone loses.

They might develop empathy.

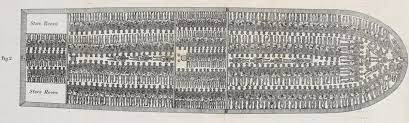

Are there other parts of history where racism played a role? Let’s consider slavery, the practice of kidnapping, buying, selling, beating, and exacting labor from another human. From as early as 1619, Black humans were brought on overcrowded ships by slave traders to the shores of this continent.

What happened next? Weren’t these ships unloaded at American docks where plantation owners bought and sold humans like cattle? Weren’t these humans forced to work to ensure the financial prosperity of their owners? Weren’t laws enacted to protect the slave owners and to allow them to use any means necessary to force these people to work for no money while living in uninhabitable conditions with little food, clothing, or health care? Weren’t most slave owners white? Weren’t most slaves Black?

Who benefitted from slavery? Who suffered? While Black people worked hard and endured abuse, were they the only ones who were adversely affected by slavery? Or did white people — slave holders, people of the community, citizens of our country — ‘learn’ through slavery that they were superior, that Black lives were expendable, that their own wealth was more important than human rights, that in order to keep and maintain their wealth, they would have to create systems and laws that safeguarded their practices, even if those practices were inhumane?

It can be hard to face the answers to these questions, unless we discover that things truly have changed. And have they?

How would you describe the experience of Black people today? Where do we see them working? Are they gaining wealth or do they continue to work hard to support the wealth of white people? In what ways has the experience of Black people changed in America? What evidence do you find for a shift in the beliefs and attitudes of white people? Do you see an acknowledgment of the impact of racism and slavery on our collective culture?

This Socratic questioning provides students an opportunity to look at the information that is presented and to interrogate it. When we ask questions, when we look for answers, we learn.

In our quest to discover how racism has shaped the American experience, we must start in the beginning with the treatment of Native Americans and Blacks imported through the slave trade, but we must then trace racism’s path through educational practices — what education has been provided for white children, Black children, Native American children, Latino children? Has any group of people received better or worse schooling simply because of their race?

We must continue to follow racism through voting practices — who first held the right to vote? When did others get to participate in elections? Are all groups of people equally able to participate in the electoral process? If not, how can it become more equitable?

We can continue our quest by exploring health care, law enforcement, the prison system, athletics, and higher education, and we can keep on going from there.

What happens when we encourage our students to interrogate both our history and our current practices, to ask: Who is benefitting? Who is hurting? Whose life is positively impacted by this action? Is anyone, intentionally or unintentionally, made to pay a price so that someone else can ‘win’?

When schools allow students to ask these types of questions, particularly about racism in our country, we will begin to see an unveiling of this sin that we often try to hide and deny. Saying that racism does not exist or that it is a thing of the past not only perpetuates the sin against people of color, it also further advances the sins of pride, selfishness, greed, and apathy among people who are white. Refusing to have compassion for all of humanity denies our own humanity.

Discussing race does not divide us — the division is already there. The only way toward healing is to expose the infection, see its pervasiveness, and get on a path toward healing. This work cannot be done in Black communities alone. White people must also acknowledge the impact of racism, the crime it continues to be against humanity, and work to expose it in all its forms and eradicate it. And the only path toward such acknowledgement is a willingness to ask some questions.

For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his soul?

Mark 8:36