Sometimes thoughts of the past can leave me sleepless. All of life has not been picture perfect, and images of brokenness can lead to pain that prevents sleep. For this reason, I often try to avoid lingering on the past, but the other night I intentionally strolled down Memory Lane for a little while. I looked at some old photos and replayed some old film. This is a new strategy for me.

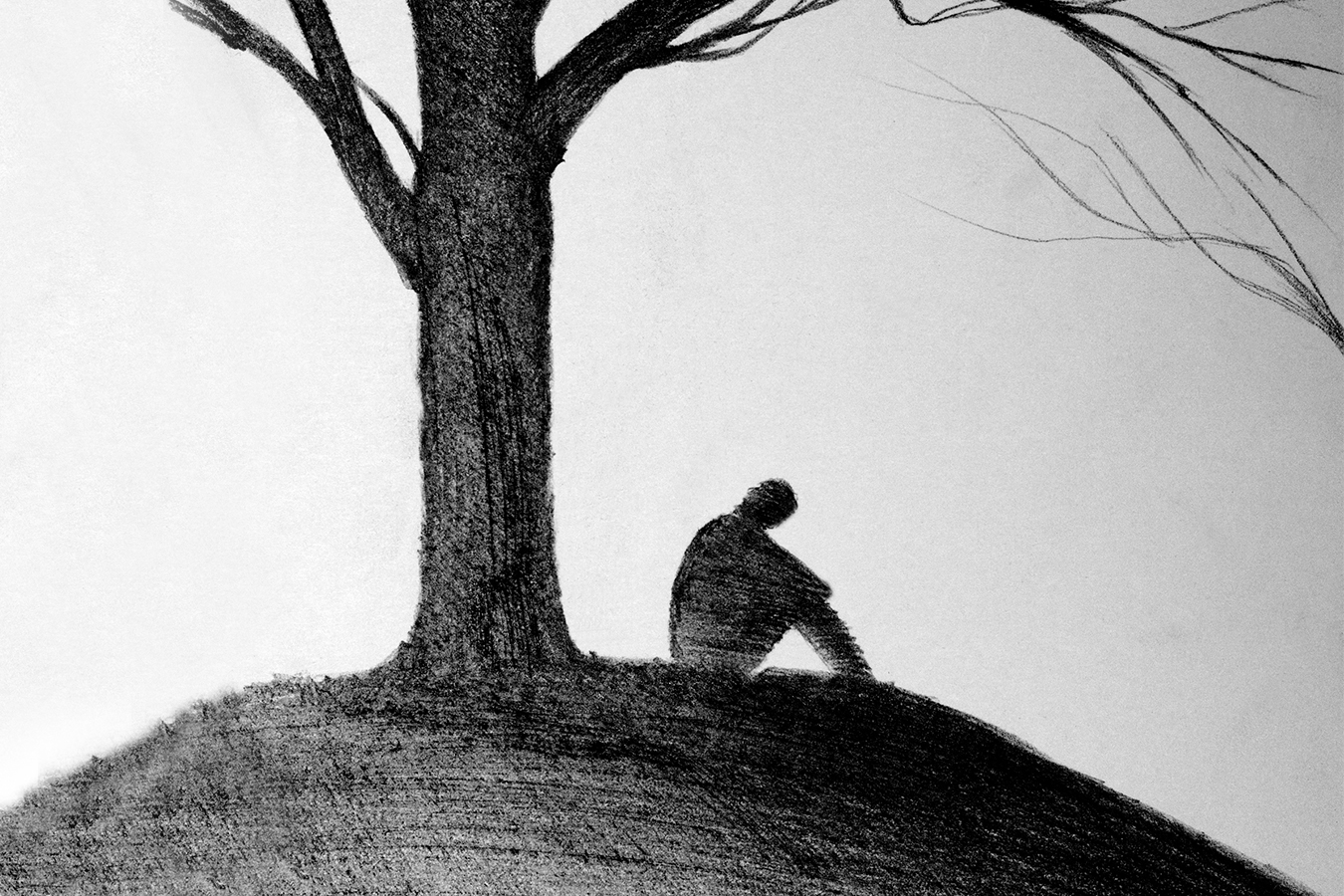

For the past several years, moments of memory have come in unexpected flashes. I can be watching a television sitcom, for example, and see a mother and daughter share a glance or break into laughter. It seems like a benign — even fun — exchange, but it sparks a memory, and I am transported back 5, 10, 15, or even 20 years to a scene where, in a moment of frustration, I snapped at one of my children when I could’ve smiled or even laughed. Later, after the television has been turned off and the lights are out, instead of sleeping, I flail amid images of that moment and others like it swirling on a screen in my mind. Rather than a stroll down Memory Lane, it feels like a free fall between black walls covered in video screens replaying moments of regret, disappointment, and failure.

Once I am in this free fall, I can go for hours. I might see myself driving a carload of kids, for example — my shoulders tensed, trying to get them where they need to go, mentally working out return trips, meals, clothing, and bills. I can feel the stress of responsibility, of course, but mostly I feel sadness and regret — realizing now how brief the moments with our children were and wanting to get some of those moments back for a re-do.

Maybe this sounds familiar. Perhaps all of us mentally cycle through memories, wishing we could go back and redo some of the moments that fill us with regret.

In families like ours that have been impacted by trauma, this experience may be even more intense. Flashes of memory may feel like mini-traumas. In my case, the flashes from the past I see often induce not only regret but also shame for my role in what did and didn’t happen.

Since I’ve made a commitment to only tell my own story, I will stay cloudy on the details, but I have shared before in this blog that our family has been touched by crime, violence, and a season of extreme overwork wherein the stress level in our household could become volatile. While I take responsibility, rightfully, for some of that stress, my brain sometimes gets confused and tries to convince me that I am responsible for all of the trauma, too. It tries to show me moments just before and just after traumatic events and to accuse me of what I could’ve done to make things different. It shows me how I might’ve prevented pain or how I should have been more active in comforting, and it continually points an accusing finger at me, showing me piece after piece of evidence where I failed as a mother, as a wife, and as a friend.

I am transported, for example, to a moment on our front porch where I asked a question but didn’t notice a detail, where I heard a response that I shouldn’t have believed. I tell myself I should have looked more closely, should’ve questioned more. I should’ve seen; I should’ve heard.

Then, I see another image, a midnight drive through the neighborhood to calm a crying teen; I see myself feeling tired, wanting to help, but not knowing what to do. I tell myself I should’ve listened more carefully, should’ve driven further, should’ve called off work the next day.

And from there, I fall to the next image…

When I am free falling through that accusatory slide show, I call it spiraling. I spin through images of moments when I wish I would’ve known more, acted differently, or seen the situation for what it really was. If only I could go back and do it differently, but I can’t, so I continue to spiral from one failed moment to the next.

Recently, as I felt I was nearing the end of a several day stretch of night-time spiraling, having had little sleep, and wanting the cycle to end, my husband, in casual conversation, brought up a topic that I thought might set me back into free fall. I said, “I don’t know if I want to talk about that. I’ve already been spiraling for several days, and I’m really ready to stop.” He was quiet for moment, and then he said, “I think it’s all part of the grieving process.”

I was silent.

It’s part of the grieving process? Going back through all these images and feeling all this regret, this ache, this shame? For the past several years, I’ve been trying to avoid spiraling, if possible, and to endure it when necessary, but if it’s part of the grieving process, I wondered, do I need to lean in and sit with it? Isn’t that what you do with grief? Sit with it?

When something dies — a loved one, a pet, a dream, a hope — it hurts, and the hurt does not go quickly away. No, it takes all kinds of mental and physical work for our minds and bodies to accept loss. We try to deny that it really happened, and we get angry that it did. We yell until we can yell no more, then eventually we cry and sob and groan as we acknowledge the loss to be real.

And, you know, we’ve got to give ourselves space for this. Loss is real — it happens — devastating, bone-crushing loss comes into our lives and we sometimes can’t bear to look at the reality of it all — but when we are ready, we must. We must look at devastation with our eyes wide open. We must see the totality of the pain and allow ourselves and all those impacted the space to grieve — to really, fully grieve.

I’ve been avoiding that full-on look; it’s been too painful to take it all in at once. However, my brain won’t let me rest until I lean in and take a closer look.

The other night, I was lying awake casually spiraling — I was too tired to be frantic, so I wearily submitted to the images that were swirling on the screen of my mind. I lay there and took it in — the accusation, the shame, the regret, and then I finally gave in to sleep.

The next morning, after my alarm jolted me awake, I wondered if it was time to shift to a different way of looking. Was it possible to instead of merely seeing the failures and sinking into shame that I might view the images through eyes of compassion — not only for the members of my family but also for myself?

When I find myself on the front porch, for example, can I acknowledge that I was home, that I was watching, that I was aware, even if I didn’t see the full picture? Can I give myself the grace to say that I was present? Can I acknowledge that to the teen, my questions were terrifying and lies were the only safe response?

When I find myself driving through the neighborhood at midnight, can I thank myself for getting out of bed, for loading a teen in a car, and for driving back and forth to allow the time for tears, even if I didn’t know what they were for? Can I have compassion on the young one who was feeling so much wrenching pain and applaud the strength it took to finally allow me to see the depth of it, even if sharing the cause of such deep hurt was still impossible?

Am I ready to make the shift from spiraling to strolling? Am I willing to slow down and look, really look, at the images? to see not just what’s in the foreground, but to see the background, the edges, and what was happening just outside the frame?

Am I ready to accept grief’s invitation to stroll down Memory Lane, to look at both the wreckage and the beauty, to see the moments of love and tenderness that sit right beside the devastation. Am I willing to see not only my failures but also the moments where I may have done the only right thing I knew to do at the time? Am I willing to believe that two competing realities can exist at the same time?

I think I’m ready to try; I think it’s the next step through this grief.

I will turn their mourning into gladness; I will give them comfort and joy instead of sorrow.

Jeremiah 31:13