**I wrote a piece called “What World Are We Living In” in the fall of 2020 when I first started commuting from Ann Arbor to Detroit to teach in a small charter school and began to daily witness the disparity between the two communities. The following post grew out of an experience I had last week in another school district.

Last Wednesday, instead of driving to Detroit first thing in the morning, I drove to Oakland County to participate in a day of professional development along with a dozen other teachers who use the Adolescent Accelerated Reading Intervention. I’ve been using the program for a little over a semester, with great results, but I have been aware that I might not be crossing all my t’s and dotting all my i’s. Having the opportunity to be a fly on the wall of two separate classrooms as other teachers implemented this intervention would hopefully help me see what I’ve been missing.

The beginning of my commute looked largely the same as it does on my daily trip to Detroit — interstate highway merging onto surface streets. However, I noted that while my regular route takes me past fast food, gas stations, minimarts, and older working class neighborhoods, this route into Oakland County took me past Starbucks, Trader Joes, and nicer restaurants before it led me through residential sections with large suburban homes. And then, when I took the final turn, I saw the school where I would begin the day.

It was a sprawling two-story building on a large piece of property surrounded by multiple well-lit and freshly-lined parking lots. I found a spot, grabbed my stuff, and made my way to the guest entrance at the front of the building. I approached a door, pushed a button, and looked into the camera before I was buzzed in to a glass-enclosed foyer.

There, a staff member/gatekeeper looked me over and buzzed me through the second door. She knew why I was there and directed me to room “two-oh-something or other”.

“Which way is that?” I asked.

“Up those stairs and follow the signs.”

I walked up the open carpeted stairway in the expansive atrium to the second floor, also carpeted, and found the group of teachers already in conversation.

They sat in a semicircle in the [also] carpeted classroom. I found a seat in the back of the room in a bar stool height chair next to a tall table. The students had not yet arrived, and the teachers were discussing what was on the agenda for the class this day — one of the final steps of reading a book in the AARI program, mapping the text.

I heard the bell ring in the hallway, and the students started coming in, finding their resources in a strategically placed filing system, then making their way to the table where I was sitting. I relocated myself and began to observe.

Right away I noticed a t I hadn’t been crossing when I looked at the big piece of butcher paper where they had started their text map. My students and I had mapped our own text the day before, and it looked somewhat similar to, if noticeably messier than, the one I was looking at, but there was one big difference — ours was written all in black on white paper. The map in this classroom was color-coded to illustrate its organization — sections of the book written in sequential order were outlined in pink, those written in a compare/contrast format were outlined in green, etc. I mentally thunked my forehead with my palm and said, “the colors! why do I always forget the colors!” And then I noticed the posters hung on the wall in this spacious classroom. At both the front and the back of the room, the teacher had full-color posters representing each of the eight text structures. Oh, I’d like to have those, I thought. If I had full color posters in my classroom instead of the black-and-white print outs I have, I might remember to use the color coding system!

One teacher asked, “Where did you get the posters?”

“Oh, I just printed them on our poster printer!”

Oh, I thought, they have a poster printer.

The class functioned mostly as my class does. The teacher had seven students around the table; one was absent. I have ten on my roster right now; typically one is absent. She used the socratic questioning that I use, and her students engaged as much as mine do, if slightly more politely, but then again, when I had a guest in my room last semester, my students were on their A game, too.

The second building was a literal carbon copy of the first, down to the same double buzzered entryway and carpeted stairs. We gathered in a classroom that “isn’t currently being utilized” where we found flexible seating — restaurant like booths, chairs on wheels at tables, and the one I chose, a rocking pod-like chair, where I noticed I could quietly shift my weight and stay better engaged in the discussion we were having before our second observation. Wow, I thought, I have some students who would benefit from chairs like these.

When the bell rang, we walked down the hall where our second teacher met us at the door and invited us first into her classroom and then across the hall to another room that “isn’t currently being utilized” so that she and her students could map their text.

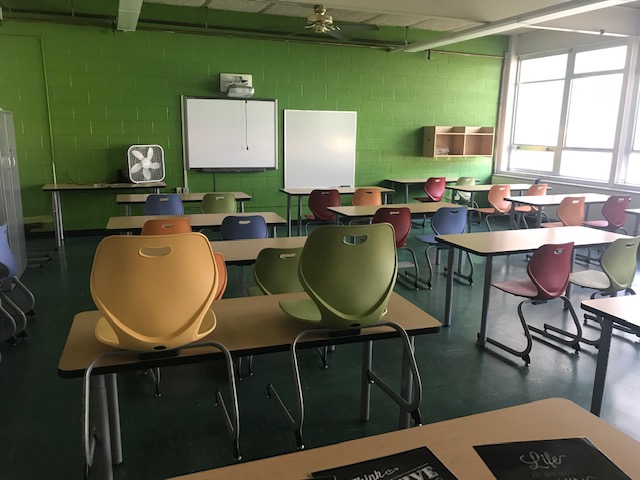

Like me, she had a projection system where she displayed a slide that she used for her gathering — the time when we engage with our students to set the climate and build community. Her students were seated, much like mine are, around the room at desks. The difference I saw was, again, the carpeted floor, the colorful text-structure posters, and stacks of resources in every corner of the room.

In the room across the hall, we again found flexible seating — bar-height chairs with optional attached desks, lower seats on wheels, and one other form of desk-like seating. Again, full-color posters on the wall illustrating each of the text structures and some key questions to ask during the AARI process.

The students again were on their A-game, and I wondered if that was the case every day, even when they didn’t have a dozen teacher-y observers. I mean, what would get in the way of their learning in an environment like this?

As I drove home, I continued wondering, why do these schools look so different from my school? Why do students in Oakland County walk into a brand spanking new building every morning, pick what kind of chair works best for them, experience the warmth of carpeting, the advantage of full-color visual aids, and, when it’s hot outside, the benefit of air conditioning, while my students just thirty minutes down the road are bussed onto a crumbling parking lot, walk into an aging building with an inadequate gym, some windows that open and some that don’t, no air conditioning, no rooms that “aren’t currently being utilized”, one seating option whether it is appealing or not, and a jillion other obstacles to learning on any given day.

Is it just a case of money?

I spent some time this morning trying to figure out Michigan’s formula for school funding that might explain this disparity — why one child’s experience is so different from another’s when they both reside in the same state. But guys, I don’t understand the model.

It’s complicated and based on per student funding from the state, property taxes, income taxes, and even cigarette taxes! Low-income (and underperforming) districts like mine are supposed to get supplemental funding from the state — which is earmarked, but historically not always allocated. And even when it is allocated, why are most Detroit schools in disrepair, lacking in resources, and understaffed when schools in higher income districts are well maintained, richly resourced, and fully staffed with high quality instructors?

Why do they get the cool rocking pod chairs and my students don’t?

Is it because those students deserve better?

No! All students deserve better! Yet these disparities continue to exist — for going on centuries now.

And why?

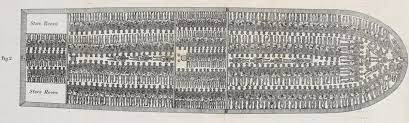

The simple answer is systemic racism — in education, yes, but also in real estate, in health care, in hiring, in so many sectors of our society. It’s the historical practice of separating those who have from those who don’t to ensure that those who have will always have and those that don’t never will. And the remedy is anything but simple. It begins with recognizing that selfishness and greed have created the structures in our country that enable some to have a lovely experience and to guarantee that others do not.

Now, if you are in the camp that thinks I am completely off base and that the difference in schools is sheer economics and not based in historical racism at all, I ask you why the establishment is so up in arms about our students learning African American history or looking at history through the lens of Critical Race Theory? If there is nothing there to see, why not let our kids take a look for themselves? Maybe you’d like to take a look for yourself. If so, I recommend you check out the 1619 Project* which is available through The New York Times, on Apple podcasts, or in video form on Hulu. And if you still think I’m out of my mind, come spend a day with me at my school. Get to know my students and decide for yourself if you think they deserve more.

Yes, I feel pretty strongly about this.

It probably won’t come as a surprise that my seniors and I just finished learning about systemic inequities in preparation for reading Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime, where we see through the lens of his experience the structural racism of Apartheid and how it impacted his childhood experience. We learned terms like unconscious bias, prejudice, racism, and systemic racism, and my students created posters to illustrate disparities in health care, generational wealth, criminal justice, and education.

When I returned to my students on Thursday and we started our class with a review of terms, I saw that not everyone understood that Apartheid was like the systemic racism we see in the US. In order to help them fully make the connection, I asked them to recall examples of where we experience inequities in our community. As they started to list them off, I told them about my experience in the Oakland Schools.

I wondered if it was necessary — to point out the details I had experienced. Would I be rubbing it in their faces?

But then I thought, Don’t they deserve to know what the experience of students 30 minutes away is like? especially as we prepare to read this book? especially since some of them are about to go to college and may study beside some of these very students who are walking carpeted hallways, sitting in rocking pods, and enjoying an air conditioned full-sized gym? (Let alone taking AP classes, music, and other electives we are unable to offer.)

I described what I had seen, and I could see their faces register the reality — the reality that their experience is not equal to the students I observed just 24 hours before.

“This is educational inequity,” I said. “It is one aspect of systemic racism. And why do you suppose it’s not easy to change?”

“Because,” one student answered, “it’s part of so many systems — not just education. And they don’t want it to change.”

“Who doesn’t want it to change?”

“The people in power.”

“Yes.” I gulped. “I suppose you are right. The people in power don’t want it to change.”

Pretty astute observation for a kid from Detroit? No. Kids from Detroit have this down, folks. They understand disparity; it’s the world they live in.

And the people in power can do something to change it. We are the people in power, my friends — people who vote, people in education, people in the church, white people — we can make choices that begin to make a difference for my students and their children and grandchildren. If we do nothing, this pattern will continue for more generations, and we shouldn’t be ok with that.

It’s not enough to fight for what’s best for our kids; we have to do what’s best for all kids.

As we established in my last post, I have “an insufferable belief in restoration.” The first step in restoration is acknowledging that our stuff is broken down, dilapidated, and no longer working, so I’m gonna keep talking about what’s broken to those who have the power and resources to fix it.

I hope you’ll start talking (and doing something) about it, too.

Proverbs 3:27

Do not withhold good from those to whom it is due, When it is in your power to do it.

*The 1619 Project is one of many places to start learning about historical systemic racism in the United States. For a list of other resources check out Harvard’s Racial Justice, Racial Equity, and Antiracism Reading List.