T minus eight days until the start of school and I’m like a 10 year old again — so excited!

Sure, Wayne County just announced that due to the recent uptick in Covid-19 cases, all teachers and students in the district will be fully masked throughout the school day.

Yes, a torrential downpour caused a flood in our school gym on Friday.

And, of course, we’re still looking to hire two staff members.

But am I bothered? No! I feel like the little girl whose mom just took her to the mall and bought her a first day of school outfit.

Why? Because I can hear you all cheering me on!

A few weeks ago, at the end of my post about Critical Race Theory, I shared that I had a wish list for my classroom. Several readers asked me to share it, and I have received almost everything on that list! I did not anticipate how much impact this would have on me emotionally! I feel buoyed your thoughtfulness and generosity!

For example, a couple of Lutheran educators from St. Louis, MO, who I have never met before, said they used to teach in Detroit and still have hearts for the kids in that community. They sent a check so that I could purchase 100 composition books!

Each day, my students will spend 10 minutes of their 100 minute block writing in these composition books. I will put a prompt on the board and provide 10 minutes of silence during which I, too, will write. I will then share what I have written, to model, and then allow anyone else to share what they have written. This exercise, which takes a total of 20 precious minutes of class time, is invaluable. It not only builds writing muscle — the ability to put pen to paper for 10 solid minutes — it also exercises the students’ writing voices and, more importantly, cultivates community. When we share our thoughts and our stories with one another, we see one another’s humanity, and we begin to care for one another. This is critical in a classroom of developing writers who will have to share their writing often.

Another item on my wish list was highlighters. I asked for 90 sets of three colors — pink/blue/yellow, or green/orange/yellow. A friend texted that she wanted to purchase all of them, and that day, Amazon delivered a huge box to my door!

These highlighters will be used in a couple of ways. For grammar instruction, I will have my students locate nouns, verbs, adjectives, or adverbs, for example, in their journals. They will highlight the word, label it, write a definition in the margin, then add several more examples. We will also use the highlighters to identify sentences, fragments, and run-ons. Later, when we are writing paragraphs and essays, students will identify their thesis and topic sentences in blue/green, their examples in pink/orange, and their explanation/elaboration in yellow.

Another item I asked for was individually wrapped snacks because teenagers are always hungry. They stop by before, during, and after school asking, “Mrs. Rathje, you got anything to eat?” I have always tried to keep something edible in my classroom because if you feed them, they will come. Seeing my request, a friend and a family member each dropped off Costco-sized boxes of granola bars and multi-packs of popcorn. A few other friends sent cash which will help me stay supplied.

I am not only stocked on snacks, but I was also able to use some of the cash that was donated to purchase large variety packs of candy which I will use as rewards/incentives for completing assignments, arriving on time, and quickly resolving conflict. I also always make sure I have plenty of chocolate to encourage other teachers in the building.

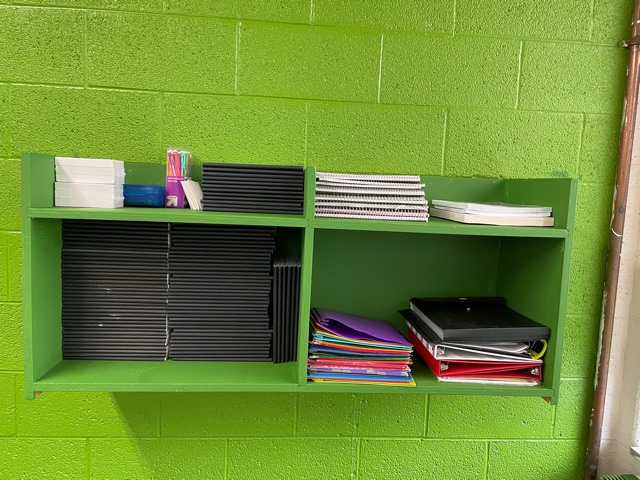

I hauled all this stuff to my classroom including several prizes donated by a family member — McDonald’s gift cards, some pop sockets, chapsticks, and the like — and found designated spaces to store it all. I was feeling pretty good about my supplies, and then, when I got home on Friday, I found a large package on my front porch.

A high school friend, who I don’t think I’ve seen in thirty-seven years, had said she was sending a few things; when I opened the box and laid its contents out on the office floor, I was overwhelmed.

She had sent boxes and boxes of feminine hygiene products, dozens of trial sized lotions and hand sanitizers, several chapsticks, packages of gum, mints, and granola bars, and some cash, in case I needed anything else. She said she “had some things sitting around just waiting to be used” and that “kids deserve to have the necessities of life…whether their parents can afford it or not.”

They sure do.

This is the family of God, my friends. People from across the country — Wisconsin, Missouri, Minnesota, and Michigan — giving what they have to meet a need. My classroom is now more than well-stocked and ready to receive a group of seniors that haven’t seen the inside of a classroom since March of 2020. As they arrive, I want them to know that I, that we, have been thinking about them, that we have prepared for them, and that we are anticipating their needs before they even walk in the room.

You have helped me do that — you have partnered with me to show my students that they are valuable.

They don’t always get that message, to be sure. And in the last eighteen months, they have lived through more than their fair share of challenges. I know they are going to have some anxiety about coming back after such a long absence, so I’ve created a ‘chill’ spot at one end of my room.

The chill spot is a place my students can move to if they are feeling anxious, angry, or upset in any way. It has tissue, paper, pens, crayons and colored pencils, coloring sheets, beautiful artwork from @mrjohnsonpaints, and some recommendations for how to regain calm. This idea is not mine; most of the teachers in my building have a chill spot. We operate under the assumption that all of our students have experienced trauma — now more than ever — so we are preparing in advance to make sure they can feel safe.

Providing for student needs — food, safety, school supplies — lays the foundation for learning. Job one is showing students that they matter, and as you have cheered me along, not only with gifts and donations, but also with so many words of encouragement and likes and shares of my blog post, you have agreed with me that they do.

My students matter, and this work matters.

They may come in grumbling and complaining. Why can’t we just stay virtual? Why is this classroom so hot? Why do I have to write in this stupid notebook? They are teenagers after all, and teenagers always grumble during change.

But I’m excited! I’ll put on my first day of school outfit and bounce into my classroom next week, ready to receive them, whether they are grumbling or not.

My enthusiasm may need to carry us for a while, so thanks for cheering me on. I didn’t know how much I need you.

…the Father knows what you need before you ask Him.

Matthew 6:8

P.S. If you know a teacher, send them a little extra love at any time, but especially during that first week of class this year. (A gift card to Starbucks or Target, some chocolate, or some fresh flowers just might make the difference.)