On Tuesday, May 24, 2022, an 18 year old carried an AR-15-style semi-automatic rifle into a school and fired shots killing 19 children and their teacher before being shot and killed by police. This was the most deadly school shooting since Sandy Hook almost 10 years ago. Following is an update of a post I wrote in response to one of countless other shootings.

On Sunday August 4, 2019, Ohio Governor Mark DeWine addressed a crowd on the same day that a mass shooting killed 9 and left 27 injured. He had just barely begun to speak when someone shouted, “Do something!” Before long, many had joined the chant, “Do something! Do something!”

DeWine was moved to action. Within 48 hours, he had proposed several changes to gun laws including a red flag law and universal background checks; his initiatives also included measures related to education and mental health. He announced his actions saying, “We must do something.”

Now that is what I’m talking about.

The people in that Dayton crowd, along with many others, are done with hand-wringing and weeping. They are tired of thoughts and prayers. They have seen enough bloodshed, and they are demanding change.

“Do Something!” they yell, and I find myself joining their cries, “Do Something! Do Something!”

Last week I wrote about prayer — the lifting up of our burdens to the One who is able to change everything.

I’m not taking that back.

Pray. Keep praying. Never stop praying.

But here’s the thing, we can pray with our breath at the same time that we are doing something.

Yes, we can have dedicated times of solitude, where we go in our prayer closets or lie on our beds and cry out to God. Do that! However, you can also put your prayers into motion. Much like you talk to a friend as you go for a run, drive down the road, or cook a meal, you can continue in conversation with God as you do something about the things you are lifting up to Him.

You can cry, “Do you see this, God? We’ve had 213 mass shootings already in 2022! We’ve had 27 school shootings this year!” while you are demonstrating in front of a governor, or writing a letter to your congressman, or donating money for mental health resources in your community or educational services at your local school or making a choice to vote only for leaders who support and will enact common sense gun legislation.

You can say, “Lord, I’m really worried about the environment, I beg for your mercy and the renewal of our planet,” as you ride on public transportation, use cloth shopping bags, or carry your compost outside.

You can sob, “I’m begging you to heal my broken relationships,” as you encourage the people you encounter every day, as you go to therapy to process your regrets and learn healthier strategies, as you do your best to rebuild relationships.

We can be people of prayer and still do something. We can do more than put on sackcloth and ashes, grieving the loss of a life we once knew. We can speak out and fight for change. We can defend the defenseless, call out the unjust, and offer solutions.

We can engage in conversations about politics — ask the hard questions, admit that we don’t have all the answers, and even change our minds.

We can volunteer in our communities — working with the homeless, tutoring public school kids, or leading clean-up projects.

We can support the people in our neighborhoods — being available, providing resources, mowing lawns, or dropping off flowers or meals.

I don’t know what your gifts are, but even while you are praying, you can do something.

Why should you? Why should you expend any effort? What difference is one person going to make any way? The problems we face are big — almost insurmountable — rampant gun violence, a drug epidemic, a decaying environment, a world-wide sex trafficking network, an immigration crisis, our dysfunctional families, and our own broken hearts.

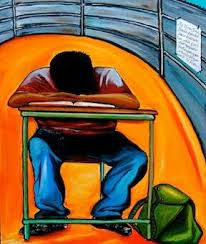

We could crawl into our beds, cover our heads with blankets, and weep as we cry out, “Come, Lord Jesus, come.”

But, friends, while we wait for His return, He is inviting us to do something.

I am not suggesting that you strap on your gear and go about butt-kicking and name-taking. Instead, I am suggesting a mindful, prayerful approach to action.

You and I can consider the items we are continually lifting up in prayer: a family member with health concerns, a strained relationship, personal debt, the environment, racial disparity, and violence against women, for example.

As we lift up these concerns, we can be asking, “What difference can I make? What is one thing that I can do? How can I help?” And we will begin to see opportunities: we can make a phone call to encourage that family member, we can respect the requests of the one who just needs some time and space, we can pay off some bills and move toward financial freedom, we can decide to buy fewer products packaged with plastic, we can vote for proposals that promote equity, or volunteer at a local women’s shelter. We can do something.

We don’t have to do everything, but we can each do something.

Imagine the impact of 10 people consistently choosing to do one thing toward improving a neighborhood, of 100 people dedicated to just one action to decrease homelessness, of 1000 people committed to improving the lives of children living in poverty.

You could be the start of transformational change, if you just decide that you are going to do something.

For the past few years I’ve been looking for something big to do. As I’ve been sorting through the broken pieces of my life, I keep trying to put them together into one redemptive action that will somehow turn my tears into wine. I want to end poverty and violence and heal all the broken hearts. I want a project, a mission, a cause.

And as I lift the broken pieces up in prayer, I hear a still small voice saying, “you don’t need to single-handedly change the world, Kristin, but you can do something. How about you just start with one small thing?”

But there is so much that needs changing!

“Behold, I am making all things new.”

I want to help!

“Act justly, love mercy, walk humbly.”

Ok. I hear you. I’ll start small, but I’ll dream big.

I’m praying that others will pick their one small thing and join me.

Whatever you do, work heartily, as for the Lord and not for men.”

Colossians 3:23

**This was written in 2019, before God answered my prayer by placing me in my current classroom and giving me a place where I can do one small thing every day.