The question of the moment around folks my age — and for the record, I’m just shy of 60– is “how much longer do you think you’re gonna work?”

My most frequent response is often something like, “I’m not in a hurry to be done. I love what I do. I hope I can stay at it a while!”

This is, of course, not how everyone feels. Many my age have put in a long, hard 40 or more years of work in jobs and careers that have taken a toll — physically, mentally, relationally, or in other ways that might make a person want to walk away.

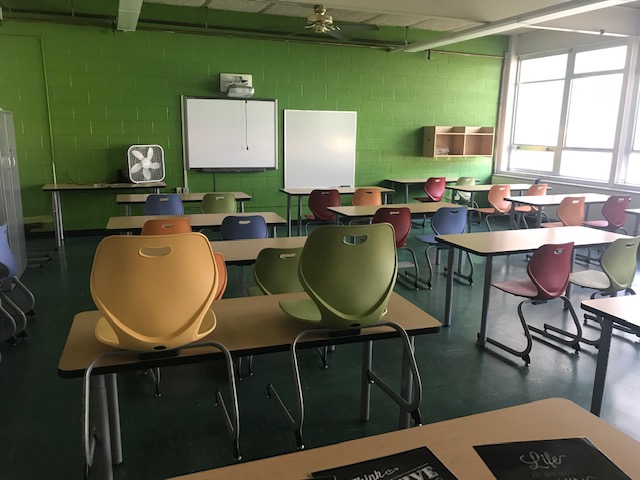

Let’s be honest, if you’ve spent 30-40 years on an assembly line — you might be ready for a change of scenery. If you’ve led a corporation and had the weight of the bottom line, personnel challenges, and inventory management on your back, you might be ready to sit by a pool, sipping a cool drink. If you’ve been in a classroom for 40 years — attending to the needs of children, designing instruction, managing behavior, and adapting to continuously changing policies, cultural norms, and learning challenges, you might be ready to just have a day that doesn’t involve managing anything but yourself.

And while I have certainly had my challenges and seasons of disillusionment and burnout, none of those scenarios truly describe me. After working in many different settings over the years, I find myself in a role that feels like a culmination — the place I was intended to arrive at, so I don’t find myself asking how much longer I want to work, but rather: When I look back at all I have learned, what do I have to offer these days?

In the early years — the first 3-5 of my career — bravado carried me past insecurity so that I could survive in situations that were way outside my experience. A middle school special ed classroom in Detroit? No problem for this secondary English major from small town Michigan! A self-contained classroom inside a residential facility teaching not only ELA but also social studies, math, science — I got this! I faked my way through and while I can’t say that my students (or I) won any awards, everyone learned something — including me. I learned about being overwhelmed and about working with limited resources. I learned to lean into the uncomfortable and to try just about anything. Did I occasionally lose my shit and come undone in front of a classroom full of typically behaving students? Sure. Did I also take a van load of Detroit teenagers on a day-long adventure to Ann Arbor? Yes, I did! Did we overfill our day with activities? Absolutely! Did we arrive back to school late after dismissal? We sure did! Did those kids and I have a ball touring a college campus, going to a hands-on museum, and eating at Pizza Hut? Yes! Rookie me swung for the fences, folks.

The bravado only carried me so far into my years at home with my own children. In fact, I think it was day one home from the hospital when I called a friend emergency-style to come save me because nursing wasn’t working out according to plan. I wish I would’ve admitted right there and then that I was clueless about mothering, but faking it until I made it was my theme song, and I just kept singing. Before I knew it, I was sitting on the living room floor with three children of my own, reading stories, learning letters, and playing games. Those days were exhausting and precious to me! We had a lot of fun, but I was making it up as I went along, so I certainly made plenty of mistakes. I pushed myself and the kids way too hard, and I expected way too much, but in continuing to give it everything I had, I learned how to schedule out a day that included learning, adventure, rest, and play; how to turn a few hot dogs and some popcorn into a baseball watching party; and how to get through a puke-filled night with little to no sleep. I learned that I could manage much more than I imagined, that I had a lot of people who were willing to help, and that it wasn’t a weakness to ask them.

When I returned to the classroom the first time, it was to a position that was far bigger than my experience — the English Department Chair and Dual-Enrollment ELA teacher at a small private high school. Not only would I, once again, be faking it ‘til I made it, I would be doing so all day long in a new environment while I was also still —at home — learning how to parent my own children who were in the process of transitioning from childhood to adolescence in a new home in a new city in a new state.The lift in both arenas was immense, but I was gonna make it happen. I learned a curriculum, read dozens of books, short stories, poems, and essays and adapted to a modified block schedule and the world of Apple computers while I also navigated the needs and ever-changing emotions of a family that was struggling to find its footing. For nine years, it seems, I was in constant motion — either preparing to teach, teaching, or grading in one space or cooking, cleaning, driving, scheduling, or otherwise parenting in another. Those years seem like a blur as I look back, probably because I never stopped running.

And then, all the motion came to a halt. Readers of this blog know that those years ended in an autoimmune diagnosis and an exit from the classroom followed by convalescence and a [next chapter] of re-learning how to live which landed me where I am now.

I came into this season humbled by the knowledge that I did I have a limit, and that I did not indeed know everything. When I was offered the position to teach ELA at a small charter high school in Detroit, I was grateful to be in any classroom at all. The fact that it was familiar territory — teaching seniors about college and the skills they would need to be successful — meant that I would NOT have to fake it til I made it. I could just be the authentic me, sharing what I know and loving the students who were in front of me. Granted, I still had much to learn — our school has an instructional model that was new to me, and I would, for the the first time in my career, have a coach, but none of that was overwhelming. In fact, it was comforting to know that I had support and that I wouldn’t have to find all the answers on my own.

That was over five years ago, and now I’m no longer teaching but coaching other teachers who may be in their very first year or nearing their 10th or 20th year. Some of them are faking it until they make it, some are disillusioned, and some are managing a lot in other areas of their lives.

I have a front row seat to their experience and that’s why I’m asking myself this question: What have I learned and what do I have to offer these folks?

I’ve learned that showing up and doing your best goes a long way — even if your best isn’t amazing, it’s likely good enough.

I’ve learned that being brave can lead to remarkable opportunities that change you forever.

I’ve learned that others are willing to support you if you are willing to ask.

I’ve learned that family is much more important than work and that your health needs to take priority over any perceived deadline.

I’ve learned that who I authentically am is much more valuable to my students and the people I love than getting every decision right or accomplishing every task.

I learned these things the hard way over the last many years, and maybe these folks — the people I rub elbows with every day and those that I coach — will have to learn them the hard way, too.

I think what I have to offer right now is the empathy and compassion gained from my own journey. I have a rare opportunity to offer support and encouragement, and the wisdom that comes with each of these gray hairs.

I’ve got perspective — each day is important but no day is definitive.

I’ve got plenty of gas left in the tank to come alongside the members of my team, to see their passion, their frustration, their hope, and their fatigue. If they are willing to keep showing up, I will, too.

Maybe I’ll get a chance to share what I’ve learned. More likely, I, too, will learn something new.

Teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom. Psalm 90:12