I’m sitting in my living room looking out at my snow-covered neighborhood. The temperatures are so low that we’ve only had school twice in the past 10 days, and it seems likely that we won’t have school for the next couple as well. Every educator loves a snow day, but if we’d had this many in my teaching days, I might be getting a little antsy by now. This many days out of school would mean my scope and sequence, my pacing, and my lesson plans would all need adjusting. The plans I wrote for two Thursdays ago would no longer be relevant. The lesson I was going to lead with today would need adjustment before we went back.

However, considering the current circumstances, I am thankful. We’ve missed four days of school out of the last two weeks, and I have been using the time — almost all of that time! — to get caught up and to get ahead.

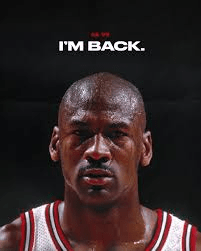

Why? Because once again I am coming off the bench. The next day we have school, I will be teaching.

Last May I taught what I thought was my last English Language Arts lesson. It probably revolved around revising and proofreading since my seniors were getting ready to submit their final high school paper. My husband, ever thoughtful, sent me flowers to mark the day. He, more than anyone, knew I’d been teaching in one venue or another since the fall of 1988 when I did my student teaching at a high school in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. While not all of those years have been in a classroom –I stepped away once to stay home with my young children then again to recover from a significant health challenge — I have spent almost all of those years teaching, writing, or instructing in one way or another.

When, due to autoimmune disease, I hung up my hat (and gave away all of my teaching gear!) in 2014, I really thought I was finished with the classroom, that I had entered retirement at the age of 48. Last spring, after five years back in the game, I really believed I was moving into the season of instructional coaching and that my days managing a roomful of teens were over. I thought I had secured my spot permanently on the bench.

Both times I was mistaken.

This past fall, I onboarded two certified ELA teachers — exactly what we needed for our small school. One would teach freshmen and seniors, the other would teach sophomores and juniors. I was so excited! Both were experienced; both were people of color! It was like a miracle!

Throughout the fall, since they were on my coaching load, I observed them teaching many times, and met with each one at least weekly. Together we began to build what I hoped would be lasting relationships.

One is getting settled into our culture. One resigned over the holiday.

This is what education looks like right now. We have more classrooms in America than we have teachers, so folks can decide midway through the year to take a different path. It can be liberating for a teacher — to know that if your current setting doesn’t fit, you have options. It can be demoralizing if not devastating for students.

In this case, the sophomores and juniors, who were without a science teacher for most of the fall semester until we found a strong candidate in mid November, are now without an ELA teacher. To complicate matters, the SAT is in less than three months. For the juniors, this the highest-stakes test of their educational career so far, and half of the test focuses on mastery of English Language Arts skills.

How, how I ask you, can we hope to overcome literal centuries of educational inequity for students who routinely experience staffing shortages throughout their educational journey — not to mention inequitable facilities, insufficient supplies, inadequate transportation, poor nutrition, and other realities of institutionalized racism. What can we — those who envision something different for these folks — do?

I came back from the holiday break with a directive (not to mention my own ass-kicking, name-taking internal drive) to support the students through the end of the semester — to make sense of where they are, to grade the work they had completed, to give some kind of a final, and to help as many as possible receive credit for the class. Three weeks and four snow days later — done, done, done, and done.

Somewhere in the course of those weeks, my supervisor communicated that I would be taking over the junior classes in the run-up to the SAT. I was to provide high quality instruction that would prepare these students to do well on that assessment. My internal desire is to also give these students — these kids who have marked time first in their Earth Science class and then in their ELA class — a good experience. I don’t want to merely get them through to the SAT; I want them to fall in love with a book, to learn the power of a growing vocabulary, to see what happens when you write down what you think, to understand the complexity of language and how it can reflect the complexity of our inner lives.

So, when the first snow day happened, I spent the day updating the grade book for these students and unpacking the curriculum I would be teaching. I will admit to a significant case of the grumpies as I began that morning. I might have been muttering under my breath about the audacity of a teacher to leave three weeks before the end of the semester without finalizing grades. I might’ve been clenching my guts in anxiety over how I was going to manage high quality instruction while still being our school’s testing coordinator (managing the SAT, MSTEP, and WIN Work Readiness tests). The neighbors might’ve heard me sputtering for the morning, but when I rounded the corner and moved from cleaning up the mess to planning for instruction, my mood shifted.

I opened up the curriculum for the class, determined I would use the text Their Eyes Were Watching God, purchased the audiobook so my students could hear the rich dialect as they followed along and annotated the text, dug into the unit plan that focuses on “figuring out yourself in a complex society” and I. was. stoked!

The ideas started pouring in. I began to picture the faces of my students engaging with the text, describing for me things that are obscure compared with things that are pervasive. I saw the connections to their lived experience, and I was energized. How would I change the classroom set up, what visual aids would I need? What tools would I use for motivation? How would I begin to build strong relationships? The gears were fully in motion.

And then we had another snow day, so I spent two days of what I thought would be a four-day MLK weekend visiting my mother and then found out that we would have another snow day to make it a five-day weekend! On that day, I prepared a final exam.

When we did have school two days this past week, I spent it giving that final exam, entering grades, and convincing these students who I had not yet taught to turn in one more assignment to get themselves across the finish line.

And then we had another day off for extremely cold temperatures. I used that time, too! Each day I tick a little off my to-do list. I’m not sure how I would’ve gotten all of this done — or how I would’ve mentally made this transition — without the time off from school!

As I finish up this post, snow is falling. Forecasters predict anywhere from 2-7 inches followed by more windchills of -20 degrees. Although no official announcements have been made, I’m going to guess I’ll have the next couple of days at home. I already know how I’m going to use them.

I’m going to audit the grade books of the teachers in our building and close out the semester. Then, I’m going to continue preparing for testing season and getting myself fully prepared for my juniors — they deserve a teacher who has intellectually prepared with them in mind, not someone who has slapped something together on short notice.

I’m thankful for the gift of all this time, and for the years and years of training that have taught me how to use it.

This old girl has still got the moves, kids, so get ready. It’s almost game time!

Before they call I will answer;

while they are still speaking I will hear. Isaiah 65:24

Would you or someone you know like to come join our team at Detroit Leadership Academy?

Want to help me supply snacks and incentives to my students?