The summer is winding down and I (along with teachers across the country) am starting to move toward the classroom.

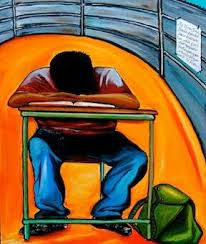

Feeling truly depleted at the end of last school year, I spent the first two weeks of summer break at home. I gardened, slept late, wrote a teeny little bit, read, walked, and cooked.

And then, when I was somewhat revived, my husband and I boarded a jet and headed west. We alit in the land of palms and headed to wide expanses of beach, spread out matching beach towels. and spent hours reading, sleeping, chatting, and staring in awe at the waves and the sky. We wandered inland and wondered at the mountains and the forests then returned to the beaches — some tame and populated, some rugged and bare.

We ate well, slept long, and walked for miles and miles.

We breathed deeply. We laughed. We restored.

When our vacation was over, he reported back to his responsibilities, and I returned to rest.

This past week, I found my way back to my desk and started to consider and prepare for the roles I will carry this fall. It will be my third year at my current school after a long season of physical and mental recovery, and it will be the most challenging yet.

Earlier in this blog, I have elaborated on the fact that many years of pushing too hard and failing to take care of myself or process any emotion had sidelined me from the classroom for several years. In 2020, I felt called back, and because we were in the midst of a pandemic, I had the privilege of easing back in through a year of teaching virtually followed by a year of some in-person and some virtual learning. I was able to get my feet under me with mostly no physical or emotional consequences until the very end of last year when my body started waving warning flags.

Those flags reminded me to fully lean into my summer, and I have. I have put puzzles together, crocheted, and binge-watched. I have rested fully, and now as reminders of all I have committed to start pinging on my phone, I am both exhilarated and anxious. I have added some new roles, and I am wondering if I will truly be able to manage it all.

I know for sure that I can manage the first responsibility, which is the one I have had from my first day at Detroit Leadership Academy. I am the senior ELA teacher, focusing on building skills that will enable my students to experience success after graduation. Our research projects focus on career and college. Our writing includes college essays and resumes. We practice academic reading, writing, discussion, and presenting. The goal is that our students will have the opportunity to choose — college, career, military, or trade school. I love this role — in many ways it is an extension of what I did in my previous classroom position, and I am thankful that I am able to carry those skills forward to support another community of students.

I also know that I can handle the second responsibility which I have had for a year now. I am our school’s Master Teacher. We have instructional coaches in our building who work directly with teachers to improve instructional practices; that is not my role. My role is more to be an exemplar and an encourager. Teachers can pop in my room and ask a question, check out my white board or room arrangement, complain about a policy, vent about a student, or ask for a snack. I love this role, too. Because I’ve been a teacher and a mom across four decades, I have seen some stuff, and not much surprises me. I can typically remain calm and objective, which is what less-experienced teachers often need.

The above two roles are familiar and natural to me, but like many teachers throughout their career, I have been offered some additional responsibilities that will absolutely stretch me in the coming year.

The first of these is one I volunteered for. I will be participating in a year-long educational fellowship wherein I will work with teachers across the state to examine educational policies and practices, do research, and work with lawmakers and constituents to enact change. I am very excited about this opportunity, which will give voice to my passion for educational equity, the key focus of this fellowship.

The second new role is to be our school’s reading interventionist and to bring a new reading program to the building. I will have one period a day with 10 freshmen who have demonstrated reading skills 2-3 years (or more) below grade level. I am being trained this week in strategies that have been demonstrated to decrease/eliminate that gap in 20 weeks of daily instruction. I am fully behind this initiative. In fact, I asked for a reading interventionist after seeing evidence of weak reading among my students. Because of my Lindamood-Bell experience, I am a solid choice (at least initially) for this role, and I know I will love watching my students develop their reading skills.

Even though I am passionate about each of these roles, they are adding up! And I haven’t even told you the last one.

After I had already accepted all of the above positions, and had begun to wrap my mind around what they would each entail, I was approached by our director of human resources and asked if I would take on an uncertified colleague as a student teacher.

Let me pause for effect, because that is what I literally did when I got the call. I sat with the phone to my ear, breathing silently.

I’ve mentioned before that 2/3 of the teachers in our building are uncertified — most, like this friend, are working toward certification. Many, like this friend, will eventually need to do student teaching. If she can’t do the student teaching in our building, she will find a different school to accommodate her, and then we would be down one more teacher.

I know it is not my responsibility, but I am the teacher in the building with the appropriate certification to supervise her, and I have had student teachers before. I believe we will work well together and that the experience will be successful, but it is a large responsibility on top of an already full load.

This is not uncommon for teachers. In fact, I am not unique at all. Teachers manage their classrooms, provide excellent instruction, sit on committees, volunteer for study groups, and support their colleagues. They coach, they work second (or third) jobs, and they also have lives away from school that include myriad challenges and responsibilities.

It’s not uncommon, yet although I am excited to get started in each of these roles, I do have some anxiety. This is the most I have committed to since the 2013-2014 school year — the year that I requested a reduced load because I was suffering with pain, extreme fatigue, and myriad other health issues, the year before I left my classroom for what I thought was the last time.

I’m not the same person I was then. I have learned how to care for my body. I am learning strategies for managing my emotions. I don’t have teenagers at home. I no longer have pets to care for. And still, it’s going to be a lot.

So here I am recommitting to my best practices — I will continue to write, to do yoga, to walk, to rest, to puzzle, to crochet, to read, and to meet with our small group. I will go to my physical therapy, chiropractic, and (now) acupuncture appointments. I will eat the foods that make me feel well and avoid those that don’t. I will limit other commitments.

More importantly, I will pray, and I will trust that God has provided me this next chapter and all the opportunities in it and that He will carry me through it all so that I can be present and fully engaged with those who are counting on me, because they truly are counting on me.

And really they are counting on the One who lives in me — the One who sees each student, each teacher, each parent, the One who knows each of our names, the One who is faithful, the One who is answering before we even use our breath to ask, the only One who can really be counted on

I may continue to feel anxious, but when I do, I will try to remember that He’s got me and all of my responsibilities in the palm of His hand.

The One who calls you is faithful, and he will do it.

I Thessalonians 5:24