On Thursday afternoon, I tidied my classroom, finalized some grades, and walked away from school and toward my Spring Break. The mere thought of not having to set an alarm for 10 days would’ve put a pep in my step if I’d had any pep left at all, but I did not.

All teachers are exhausted by this time in the year. Even though we had Christmas break, even though we might’ve had a long weekend or even a full week off in February, we’ve been, since September, coordinating learning for our students, planning multiple presentations each day, keeping records, reporting to our supervisors, and (and this is the most draining part) making countless in-the-moment decisions:

What is the first thing I need to do when I walk in the door?

Do I have an extra stapler, know where more chart paper is, and can I laminate another hall pass for Room 117?

No, you can’t go to my classroom unattended; yes, I can get you a bandaid; no I don’t know where Mr. Smith is,

You can’t go to the bathroom right now, but ask me again in 10 minutes.

Yes, you can take that pencil, borrow that book, eat that snack.

You sit over here; you stay there.

Yes, your topic sentence is solid, but no, that is not an adequate example.

You’ve used AI here, and you must re-do the assignment.

You’ve used AI here, and you cannot re-do the assignment.

Yes, you can turn it in late. No, the deadline has passed.

Yes, you can work with a partner. No, you can’t get the answers from a peer.

This is non-stop all day long, but teachers, while keeping this decision-making machine running, must also, intervene in interpersonal conflicts, address misbehavior, meet demands for mandatory documentation, and, oh yeah, provide high quality instruction.

And most of us are happy to do all of this. We see each piece as necessary for supporting human development, for preparing the next generation of humans for meaningful life in our society. We’re teaching our students to co-exist with one another, to manage themselves, to hold themselves accountable, to read, to write, to identify a career, and to begin to take steps toward attaining that career. We’re in this work because we like kids but also because we believe in the power of education to create possibility for students of all backgrounds and abilities and to create a better future for all of us.

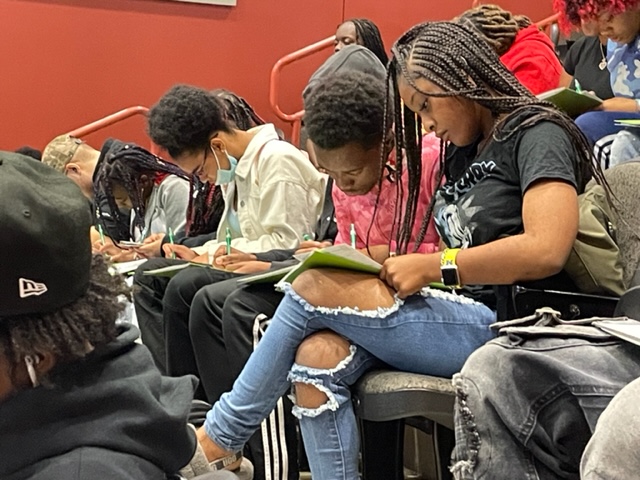

In the school where I work — a small charter school on the edge of Detroit, where 99% of my students are Black, where 100% of the students qualify for free breakfast and lunch, where almost all of the students are below the national average in reading and math scores by no fault of their own but because of centuries-long inequity in education–the teachers, like me, believe in the transformative power of education. We see it as an opportunity to not only change lives but to save lives.

In addition to the exhausting work that teaching is in any context, teachers in buildings like mine have the added weight of wondering if our kids have enough to eat, if they have a home to sleep in, if their home is safe, if they will have what they need for the next 10 days, or if they will be alone, hungry, cold, or in danger. Our students have the same needs as any students in the country, but they have additional needs as a result of poverty that stems from systemic inequities that go back through the history of our nation — school segregation, red-lining in real estate, unconscious bias in hiring practices, and other elements of historical and current systemic racism.

So, you might imagine how I am feeling, heading into a much-needed break while simultaneously worrying about my students’ welfare, to learn that the president of this country has ordered the Director of the Department of Education to dismantle it.

You may say, “Settle down, Kristin, most funding for education comes from the state.”

That is true, most money for education comes from the state — but do you know what does come from the federal government? Funds that make a difference for students like mine. For example, Title I, which provides $18 million to low-income districts. It’s not enough to make up for the economic disparity between neighboring districts, but it’s a start. The Department of Education also provides IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) funds to the tune of $15 billion to help districts provide additional resources to students with learning disabilities, cognitive impairments, and other diagnoses such as autism. Source.

Furthermore, the US Department of Education manages Federal Student Aid for post-secondary education, providing over $120 billion annually in grants, loans, and work study that allows students like mine to dream of a career. And not just students like mine — I myself relied on federal money to get my degrees, didn’t you? Source

Can you imagine what might happen in communities across the country if high school seniors no longer have access to the FAFSA? if they can no longer apply for federal dollars to fund their education through grants and/or loans? Tuition alone for Michigan State University is over $16,000 a year. Add in room and board and your talking about $35,000+. Most students need at least four years to get a basic degree. Who among us can fund $140k without the aid of at least a student loan?

Now, the State of Michigan is prepared to fund up to two years of community college and up to $5,500 per year at state universities, but states rely on the federal mechanism of the FAFSA to distribute those funds. If the DOE is dismantled, how long will it take for states to pivot to their own systems to ensure that students who need these funds get them? And, where will students borrow the balance that is not covered by state funds if they don’t have access to federal student loans?

How many students will take post-secondary education right off the table — including trade school programs that prepare our electricians, plumbers, welders, builders, and the like?

As I consider the potential outcomes of such action, the faces of my seniors are appearing in my mind — J. who wants to be a programmer, who has already completed several summers developing coding skills, L. who plans to be a nurse, K. who wants to be a truck driver, and S. who plans to become a police officer. None of these students can take one more step without the FAFSA and right this minute the Secretary of Education (who has zero experience with issues that impact schools) is busy laying off DOE employees under a directive from the president.

I am exhausted, and it’s my Spring Break, but I can’t just sit by and watch this happen.

So, I’m doing two things: First, I’m writing this post, and second I’m committing to use the app “Five Calls” to involve myself in the American process.

Here is how it works. Download the app, select the issue you are concerned about, and enter your zipcode. You will see a timeline of updates on that issue and a list of representatives from your district. One click later, you will see a page like this:

You click on the number, wait for an answer, read the script, and and click a blue button to register whether you left a voicemail or made contact, and the app sends you to the next number.

In just a few moments this morning I made three calls.

This may seem like something small — just like my boycotting may seem small and ineffectual to some –but if we truly believe that our government is of, by, and for the people, then we, the people, need to get involved. We need to do something when we see that our government is not representing all of the people — particularly when they are taking steps to further disenfranchise the most marginalized among us.

Look, you’re probably exhausted and overworked, too. You might feel like this is not worth your time, but perhaps you can take a journey back to your high school self, remember what it feels like to have a dream in front of you — of a career, a family, a whole adult life. Remember what that feels like? Don’t we want to make sure that every kid in America has an opportunity to pursue their dreams?

If you believe in the transformative power of education like I do, I urge you to make 5 calls — today, tomorrow, and until our voices are heard.

It’s a small decision you and I can make that could make a monumental difference for our kids, our country, our future.

Speak up … defend the rights of the poor and the needy. Proverbs 31:9